Tina Sanilla Aikio can’t remember a hotter summer. The area around Inari in Finnish Lapland is hot and dry during the midnight sun months. The coniferous needles at the tips of the branches, which should originally be deep green, are orange. The moss on the forest floor, which was usually swollen with water, has dried up.

“I spoke to many elderly reindeer herders who have never experienced heat like this summer. The sun continues to shine and it never rains,” said Sanila, former president of the Finnish Sami Parliament.・Aikio says:

Here in the Sami homeland, the boreal forest takes so long to grow that even small, stunted trees are often hundreds of years old. It is part of the taiga (meaning “land of little sticks” in Russian), which stretches across the far northern hemisphere through Siberia, Scandinavia, Alaska, and Canada.

These forests helped underpin Finland’s commitment to become carbon neutral by 2035, the most ambitious carbon neutrality goal in the developed world.

law enacted 2 years agomeans the country aims to reach the target 15 years earlier than many EU member states.

in a country 5.6 million people and almost 70 percent Many people thought the project was safe because it is covered in forest and peatland.

Wooden vaulting: A simple way to combat climate change that you’ve probably never heard of

For decades, the country’s forests and peatlands have reliably removed more carbon from the atmosphere than they emit. But starting around 2010, the amount absorbed by land began to decline, first slowly and then rapidly. By 2018, Finland’s land will sink (a term scientists use to refer to something that absorbs more carbon than it emits). It was gone.

that forest sink I declined About 90% fell from 2009 to 2022, with the remaining decline driven by increased emissions from soil and peat. In 2021 and 2022, Finland’s land sector made a net contribution to global warming.

Climate change impacts across Finland are dramatic: despite cuts 43% reduction in emissions Net emissions for all other sectors are approx. Same level as early 1990s. It was as if nothing had happened for 30 years.

This collapse has huge implications not only for Finland but also internationally. at least 118 countries Relying on natural carbon sinks to meet climate goals. Now, due to the combination of human destruction and the climate crisis itself, some people are reeling and starting to realize that the amount of carbon they are taking in is starting to decline.

“You cannot achieve carbon neutrality if the land sector is a source of emissions. Other sectors cannot reduce all emissions to zero, so they must be sinks,” the government official said. Juha Mikola, a researcher at the Natural Resources Institute of Finland (Luke), who is responsible for compiling the statistics, said:

Georgia activists call for greater protection of salt marshes, a major carbon sink

“When these targets were set, land removal was around 20 million to 25 million tonnes and we thought the targets were achievable. But now things have changed, mainly because: “The land absorption of forests has decreased by almost 80 percent,” he added.

Luke researcher Tarja Silfver said: It’s really, really hard. ”

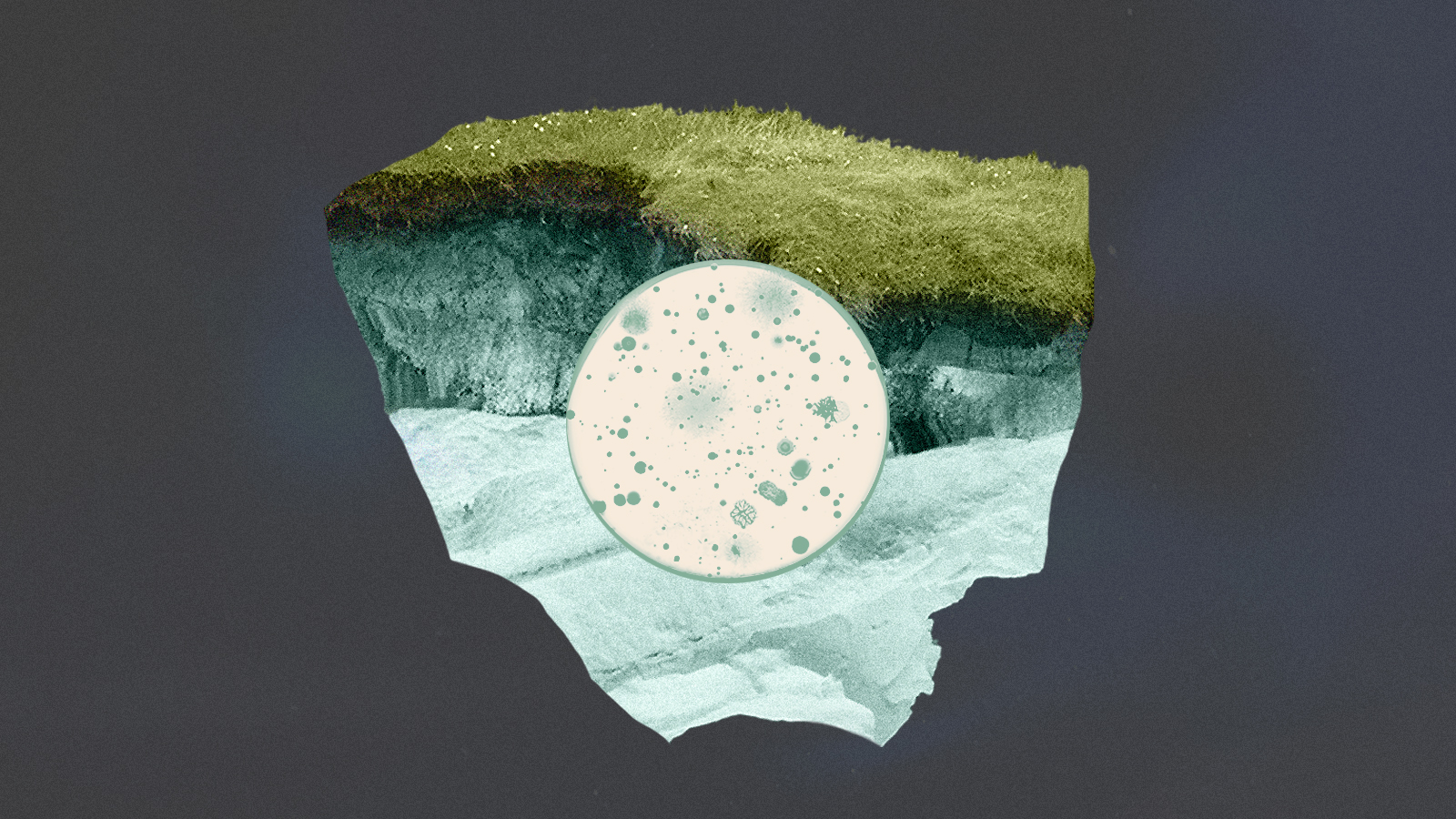

Researchers say the reasons behind these changes are complex and not fully understood. Burning peatlands for energy is more polluting than coal and remains common. Commercial logging of forests, which contain rare native ecosystems formed since the last ice age, is already increasing at an unrelenting pace and accounts for the majority of emissions from Finland’s land sector. But there are signs that the climate crisis is driving the decline.

Rising temperatures in the fastest warming region on earth are heating up Finland’s soils and increasing the rate of peatland decomposition and release. greenhouse gas into the air. Parsus Huge mountains of frozen peat are rapidly disappearing in Lapland.

The number of trees dying has also increased in recent years as forests are stressed by drought and high temperatures. In southeastern Finland, the number of dying trees is rapidly increasing. 788% increase in just 6 years Between 2017 and 2023, the amount of standing dead, or decaying, trees increased by about 900%.

Most of the country’s forests were planted after the end of World War II, but they are also mature and approaching the maximum amount of carbon that can be stored naturally.

Battle of the Swamps: Farmers and EU face off over Ireland’s biggest carbon store

Bernt Nordman of WWF Finland said: “Five years ago, the general view was that Finland’s forests were a huge carbon sink and that forests could actually offset Finland’s emissions. This has changed very, very dramatically. I did.”

These changes, predicted by climate scientists, are worrying policymakers. Finland is not alone in experiencing decline and land subsidence. France, Germany, czech republicSweden, and estonia They are among the areas where land absorption is significantly reduced.

In addition to pressures from forestry, drought, climate-related bark beetle outbreaks, wildfires and tree death due to extreme heat are devastating Europe’s forests. The amount of carbon that land sequesters across the EU each year will fall by around a third between 2010 and 2022, putting the continent’s climate goals at risk, according to new research.

Johan Rockström from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research said: [for Finland’s shift] Although not well studied, it is very likely a combination of unsustainable forest management and mortality due to drought and extreme weather events. A similar trend is seen in Canada, mainly due to disease outbreaks, but also in Sweden.

“These countries are located in the warm north and are considering carbon sinks as central to their climate policies,” he says. “This is a very big risk for these governments.”

In Salla, southern Lapland, Matti Riematainen and Tuli Harinen walk through the remains of a rare old-growth forest. Black lichen hangs from the branches above a giant, waist-high ant nest. On either side of the muddy road, dead gray trees stand in a sea of green. Forest activists say this shows the area has never been disturbed by humans.

What your gut and Arctic permafrost have in common and why it’s an alarming sign of climate change

However, the road they are on has just been cut down, and is a forest road used by loggers. Behind them lies a barren clearcut dotted with stumps and bare fields. Soon, the surviving trees will be turned into pulp.

As part of their cat-and-mouse game with forestry, Riimatainen, a forest campaigner with Greenpeace, and Hakulinen, a project manager with the Finnish Society for the Conservation of Nature, traveled to remote forests to document the rare species that live there. They hope to block factories from obtaining sustainable timber certification and give forests a reprieve by proving the presence of endangered wildlife.

“This is part of a vast virgin forest that was logged last winter,” says Riematainen, pointing to the vast expanse of forest that was cleared.

Some of Finland’s forests are considered untouched and are often found in or around peatlands, but there is little formal protection from the government. New areas are regularly cleared for pulp and timber.

Researchers say slowing the rate of deforestation, better protecting intact ecosystems and improving forest management could help Finland reverse land subsidence. However, the cost has led to opposition from the forestry industry.

Finnish Ministry of Finance estimate A one-third reduction in crop yields would reduce GDP by 2.1% and cost between 1.7 and 5.8 billion euros ($1.84 billion to $6.28 billion) a year. Strengthening forest protection would cost the country hundreds of millions of euros. According to Finnish nature panel. state owns 35% of the forestthe rest is owned by private owners, companies, municipalities, and various organizations.

The future of U.S. forests, major carbon sinks, is ‘highly uncertain’

A major Finnish timber company said it acknowledged that the country’s forests still absorb more carbon than it emits, but that the amount has fallen dramatically in recent years. The biggest threat to the climate, they say, is not forestry but fossil fuels.

A spokesperson for Metsä Group, a cooperative of more than 90,000 forest owners, said that each time a forest is cleared, a new tree is planted, which could increase carbon sequestration in the long term. He said there is.

A spokesperson for Finnish forestry company UPM said the 2035 carbon neutrality target was too optimistic and said “climate policy expectations are focused too much on sinks in the land-use sector.”

“Calls for limits on logging often overlook the point that the state owns about a quarter of Finland’s forests. The government accepts significant direct and indirect financial consequences. If they wish, they can restrict harvesting on their own land,” they say.

Under the right-wing government elected last year, there has been less emphasis on meeting climate change targets. The Finnish government did not respond to the Guardian’s request for comment.

But researchers warn that rising global temperatures could make Finland’s land subsidence even worse. Research shows that across northern ecosystems, Forests are losing their ability to absorb and store as much carbon as possible.

“There are some very serious scientific scenarios in which Finnish spruce will not be able to survive, at least in southern Finland, if climate change continues,” says Nordmann. “The whole forestry system is based on this tree.”

For communities that have always lived in the Arctic, the changes are already evident. As autumn approaches, reindeer at Sanila Aikio are preparing to return from their summer feeding grounds for an uncertain winter.

She explains that when the drought continues, there are no mushrooms for the reindeer. “If you don’t gain weight, you’ll starve,” she says.