Photo essay

A series of dams and decades of conflict have transformed the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that gave birth to some of the world’s oldest civilizations, so Kurdish photographer Murat Yazar turned his lens to these rivers and the people who live along them in his homeland.

what Not yet Did it flow into the Tigris and Euphrates rivers?

Raindrops. Blood. Meltwater. Ash. Hope. Pesticides. Ink. (When the Mongols sacked Baghdad in 1258 A.D., they threw so many books from the city’s libraries into the Tigris that the river’s current ran black with ink.) Dreams. Stories. Time.

Photographer Murat Yazar understands this. He knows that rivers are the biographers of their landscapes. They carry within their course a swirling distillation of all the events and anecdotes that have happened in the settlements they pass through. And few rivers convey history, stories of human woes and triumphs, more densely and solemnly than the Tigris and Euphrates, legendary waterways that flow through the heartland of Eurasian civilization, threading the Fertile Crescent from their cold headwaters in the mountains of Turkey, through the vast basins of Syria, Kuwait and Iran, and finally emptying into the Persian Gulf on the sweltering marsh shores of Iraq.

Ten years ago, I walked with Yazar along the Tigris River in the ancient settlement of Hasankeyf, Turkey. Çoban Ali Ayhan There he sang me an old ballad, a cry of pure anguish. His voice echoed through the sandstone canyons of the Tigris, a hymn to true love – love unrequited. It was an ode to loneliness, to waiting, to the exquisite agony of betrayal. In other words, a song fitting both for the ancient riverbed and for the town soon to be lost beneath the reservoir of yet another gigantic government dam. HasankifOnce lit by Neolithic campfires, the site, along with the ruins of nearby fortress walls, ornate minarets and cliff-top citadels, will soon bear witness to some 12,000 years of Roman legions and Silk Road caravans.

Yale Environment 360

“What can we do?” Ayhan told us gloomily. “We were against the dam. It’s going to be built anyway.”

Currently, the location is underwater.

In his documentary photography project, “Paradise Lost,” Yazar presents us with the human and environmental costs of the massive redevelopment of Turkey’s Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

Yazar’s eyes are always on the home front. He is a Kurd from Şanlıurfa, Turkey, the son of generations of shepherds. For him, his human connection to the landscape of his childhood is sacred. His hometown has literally been transformed beyond recognition by the construction of hundreds of dams, canals, barrages, and large and small diversion projects. Turkish authorities claim that the millions of tons of concrete poured to develop these rivers are essential for agricultural self-sufficiency, irrigation, and the hydroelectric power needed to reduce the country’s reliance on foreign energy.

But Yazar paints a picture of a pastoral Mesopotamia, “the land between two rivers,” that is rapidly being transformed by flooding, village relocations, large-scale mining projects, deteriorating water quality, and dramatic climate change that is limiting the flow of the two life-giving rivers that have long sustained the region’s diverse cultures.

Murat was working on the project in Iraq near the Turkish border this summer when he was arrested by Kurdish security forces, who confiscated his camera and detained him for nine days.

As I hiked with Yazar along the banks of the Tigris, a fragile truce between Turkish forces and Kurdish separatists was unraveling (the region has since been hit by devastating military operations), refugees were flooding into Turkey from war-torn Syria, and the regulated waters of the Tigris and Euphrates were channeling through countless pipes and concrete channels into the remote town of Basra, home of Sindbad the Sailor.

But even now, all is not lost.

Through sensitive portraits of rugged riverside communities struggling to adapt, Yazar’s photographs remind us that there is still time to protect what remains of the region’s ecosystems and traditional ways of life. Yazar’s photographs are more than just a lament; they are a call to action.

Scroll down to see the images or click on the photo below to launch the slideshow.

The Euphrates River near its source in Türkiye.

Cihan Çal tended his sheep near the Keban Dam reservoir on Turkey’s Euphrates River, while the farmhouse behind him was abandoned after the dam flooded its pastures.

Karakaya Dam on the Euphrates River.

Residents of Hasankeyf, Turkey, visit the remains of their former homes along the Tigris River, which were submerged by the Ilisu Dam in 2020.

An oil field in Hasankeyf, Turkey.

A man washes a horse at the Ataturk Dam reservoir on the Euphrates River.

The canal carries water over 100 miles from the Ataturk Dam to Kiziltepe in Türkiye.

Ahmet Yilmazsoy says his 450 pistachio trees died after water from Turkey’s Ataturk Dam reservoir flooded into his town in 2017. Farmers use water extracted from the Euphrates River for irrigation, but rising groundwater levels are damaging drier-loving crops.

Part of Türkiye’s city of Çekeme, located on the Euphrates River, was submerged after the Bilecik Dam opened in 2000.

Farmers dry tomatoes in Sibelek, near the Euphrates River, Turkey.

A cyanide pond at the Chopra gold mine near the Euphrates River in Turkey. Cyanide, used to separate gold from ore, began leaking from the site in 2022, and in 2024 nine workers were buried and killed in a landslide of contaminated soil.

Abzel Mahmoud is a 12-year-old Roma boy from Bismil, Turkey, whose family fled the Syrian civil war and now spends most of the year in a tent camp along the Tigris River.

Where the Tigris River divides Turkey and Syria, Turkish authorities have built a border fence to stop illegal crossings.

Fisherman Muhammet Nemriq said the reservoir of the Mosul Dam on Iraq’s Tigris River had shrunk dramatically because of the drought.

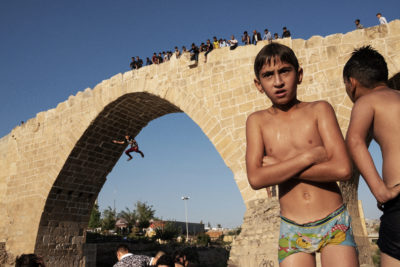

Children play under the Deral Bridge over the Zebir River, a tributary of the Tigris, in Zakho, Iraq.