(Image credit: Courtesy of Sally Tawil and Ralph Tawil/Nara Yoshitomo Foundation)

How Japan’s “most famous” artists and others are subverting the country’s cute “kawaii” aesthetic and questioning the world we live in.

Ma

Over a thousand years ago, the Japanese Empress Fujiwara no Teishi gifted one of her court ladies, Sei Shonagon, with a fine stack of paper. Coming from a literary family, Sei Shonagon used the scraps to record her observations of everyday life, eventually penning the collection now known as The Pillow Book (1002). In one passage, Sei Shonagon wrote a list of “adorable” or “beautiful” objects, from baby sparrows that “hop around” to children that “cling to whoever picks them up” to simply “any small thing.”

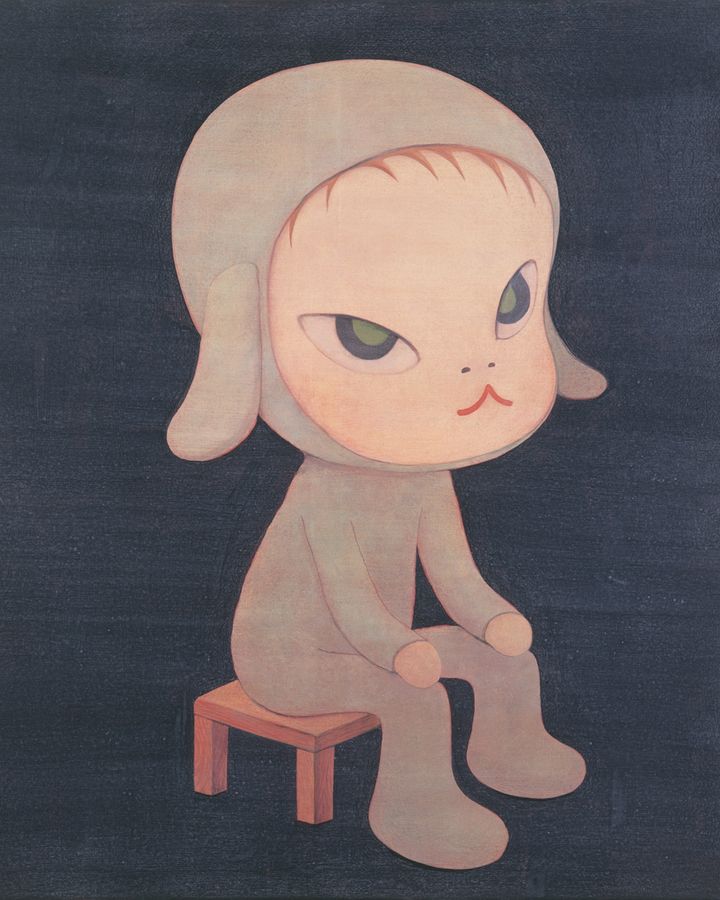

Sleepless Night (sitting) (1997) – Yoshitomo Nara’s figures deviate from the conventional ideal of childlike “cuteness” (Photo courtesy of the Louvre Museum/Yoshitomo Nara Foundation)

Today, the book is seen as a window into the aristocratic society of Japan during the Heian period (794-1185 AD), but Qing’s ideas about “beautiful things” still resonate today, and it’s considered one of the earliest examples of Japan’s “kawaii” culture, even though the word “kawaii” wasn’t in the Japanese vocabulary at the time. “All the items on the list are things that we would still consider cute today, which is remarkable considering that society was quite different in Japan 1,000 years ago,” says Joshua Paul Dale, a Tokyo-based professor of kawaii studies at Chuo University. “It’s a very complete record of the kawaii aesthetic that existed before the word kawaii even existed.”

“Kawaii,” as we know it today, originated in Japan around the 1970s and has since become a phenomenon known worldwide for its colorful, childlike aesthetic found in fashion, art (especially manga), and everyday memorabilia. But as the trend has expanded, a wave of contemporary Japanese artists have begun using aspects of kawaii to create paintings that explore different aspects of society or grapple with personal, national, or global trauma. “There are a variety of hybrid categories that experiment and subvert the kawaii aesthetic,” says Dr. Megan Catherine Rose, a cultural sociologist at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, noting that these emotionally complex works of art often “bring together seemingly disparate expressions to give voice to dissonances that arise in everyday life.”

Artist Yoshitomo Nara sits in front of his work “TOBIU” (2019) (Photo: Ryoichi Kawajiri/Courtesy of the artist/Blum & Poe/Pace Gallery/Yoshitomo Nara Foundation)

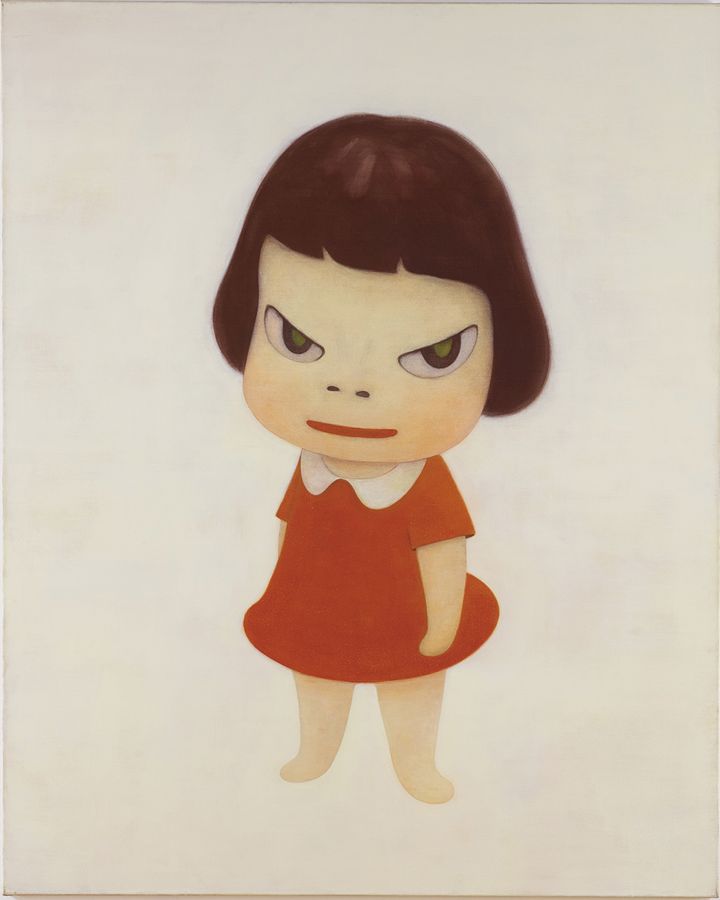

One of the most common examples of this type of painting is “Knife Behind Back” (2000) by Japanese painter Yoshitomo Nara. $25 million at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in 2019. Nara is Nara has been described as “perhaps the most famous living contemporary Japanese painter.” The painting is one of Nara’s most distinctive portraits, depicting a small, wide-eyed girl with cropped brown hair, a red dress and an almost threatening scowl. The work is part of a large collection of similar works that Nara produced over the decades. “Nara’s ‘Girls’ are figures of contrast,” art historian Ewan Kuhn wrote in a 2020 monograph, noting that Nara created “a group of big-headed figures whose behavior deviates from conventional ideals of cuteness with aggression, irreverence and wit.”

Expressing emotions

Although it might not be obvious from looking at his work, Nara is constantly influenced by “things that have nothing to do with art”, he told the BBC on the opening day of the Yoshitomo Nara retrospective at the Nara Museum of Art. Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain Until November. Instead, Nara says he draws inspiration from adventures like “visiting Syrian refugee camps and going to Afghanistan,” explaining that in the ’90s, he would paint around 120 pictures a year, expressing feelings he found difficult to put into words through his work. “I started by remembering the feelings and emotions I had as a child, but gradually I began to look further afield, learning about society and traveling to different places.”

The recent “Cute” exhibition at Somerset House in London explored cultural ideas around cuteness and kawaii (Photo by David Parry, PA, Somerset House)

Nara says his childhood experiences were positive, but his work is heavily influenced by the loneliness he felt growing up in Hirosaki, a rural town near a U.S. air base, more than 400 miles from the nation’s capital, just after World War II. His brothers are seven and nine years older, and Kuhn says that Japan’s “rapid socio-economic changes” at the time meant that Nara was often alone at home, with both parents working demanding jobs. “Growing up on the geographic edge of Honshu after the war shaped his sense of self,” Kuhn explains, noting that he especially “connects with people who come from the border or who have fled to the border.” Dale adds: “Artists love complexity. They don’t usually want to provoke simple emotions in people. So… [Nara] Adding other elements to the “kawaii” that is all over Japan [emotions] Please go in there.”

Shaped by postwar experiences, the art has also been associated with the Japanese Superflat movement, famously known as Artist Takashi Murakami Murakami coined the term Superflat in the late ’90s to describe a wave of artists who blended high and low art, particularly work that incorporated the kawaii and manga-style motifs that were popular in post-war Japan. “World War II has always been a theme of mine. I was always thinking about how culture was reborn after the war,” Murakami said. The New York Times, 2014. Haruki Murakami’s “Tantanbo: In Communication” (2014) Two creepy versions The artist’s signature character, Mr. Dob, A sharp-toothed character inspired by Mickey Mouse, in Tambor’s work the character is almost completely transformed into two monstrous creatures with drunken eyes and huge black teeth, with other creatures seemingly living inside them.

Takashi Murakami’s work was exhibited at the 2020 design fair, where he coined the term “Superflat” (Credit: Getty Images/Courtesy of the artist)

Murakami says that “Tan Tambo – In Communication” was created in response to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, which subsequently led to the Fukushima nuclear disaster. For many Japanese artists, this period was a pivotal one in their practice. “It was an opportunity for Japanese artists to reflect on the social and ameliorative potential of art,” says cultural scholar Hiroki Yamamoto, currently the curator of the Japan Pavilion at the 15th Gwangju Biennale. “As a result, throughout the 2010s, primarily young Japanese contemporary artists produced works that critically explored Japan’s (largely forgotten) history of imperialism and colonial rule during World War II, and the ‘legacy’ that this history has created in contemporary Japan.”

Aya Takano, one of the best-known artists in the Superflat movement, says her work before Fukushima was “really shallow”, but now she sees Japan more broadly than just its cities, producing work that is “really limitless and rich”. 2015 painting “The Galaxy Inside” Featured in An exhibition of cuteness, adorability and contemporary culture The painting, which was exhibited at Somerset House in London earlier this year, shows a wide-eyed, androgynous young woman suspended in space surrounded by planets and adorable, smiling, chained animal-like creatures. She says her paintings explore the climate crisis and depict a world where humans and nature coexist peacefully.

Yoshitomo Nara’s “Missing in Action” (1999) is one of the works currently on display at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. (Photo: Sally and Ralph Tawil/Yoshitomo Nara Foundation)

According to cultural sociologist Dr. Megan Katherine Rose, Japanese feminist artists have also used kawaii in this way. “Kawaii as a gendered aesthetic has been used for centuries to curate and present the female body as beautiful, similar to the treatment of women in traditional European art,” she says, adding that contemporary Japanese feminists often use art to “interrogate the objectification of the female body.” Dr. Rose cites the example of US-based Japanese artist Mizuno Junko, explaining that “her figures are fearsomely feminine, designed to repel the cisgender heterosexual male gaze through repetition, exaggeration and exaggerated femininity.”

And something closer to this:

• Photos that criticize British specificity

• Coquette: The controversial and ultra-girly movement

• Inside Japan’s most minimalist homes

Nara is also known for his cute but menacing paintings, an association he doesn’t necessarily subscribe to. He’s wary of being pigeonholed into specific artistic canons or movements like Superflat, kawaii, or cute, but he understands why others might associate him with these. “There are people out there who are superficially influenced by my paintings and maybe think they’re cute,” he says. “They probably aren’t going to go to a refugee camp or take part in anti-war protests.” [like I have]”If you asked me to draw a cute picture I could do it, but it would be completely different from what I’m drawing now. “What his work, along with many others, shows is that cuteness can be used as a tool to question the world we live in, especially in its darkest moments – a technique that many Japanese artists have mastered.

Yoshitomo Nara will be at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao until November 3, 2024

—

If you liked this story, Sign up for the Essential List Newsletter – We’ll send you handpicked features, videos and can’t miss news in your inbox twice a week.

For more culture coverage from the BBC, Facebook, X and Instagram.

;