Vince Jones

Vince JonesIn pockets in the UK countryside, you can stumble on clusters of beautifully designed Scandi-style cabins. These are not the products of the latest trends in off-grid retreats, but were created half a century ago by Welsh architect Heard & Brooks. How did they get held in creating the perfect holiday home? And why were they so inspired by Denmark?

By the 1970s, John Heard and Graham Brooks had already received many major awards for a sophisticated modernist postwar villa in the valley of Glamorgan of Glamorgan in Wales. However, a high point in their careers was the prefabricated timber cabins that they designed in the 1970s and 1980s for holiday parks in Scotland and holiday parks in Cornwall and Yorkshire’s UK counties.

For Brooks, the cabin was an opportunity to diest the spirit of his design into the clearest, purest, most compact form, says Peter Halliday, co-author with Bethan Dalton. Cabin Crew: The Pursuit of the Perfect Holiday House with Hard & Brooks. “He was able to eliminate the troublesome essentials of home remedies that must be housed in traditional homes, and he was able to focus on what was really important.”

Ian Brooks Collection

Ian Brooks CollectionThis is reflected by Professor Richard Weston, an architect and former architectural committee chair at Cardiff University. “[Brooks] He always said that the Holiday Cabin was the highlight of his career. “He wrote in the book: “They are all distillations that Graham supported. Love of wood, appreciation for proper architecture, the direction of the sun, and the feel of the universe – everything was stripped for essential life.”

Hird & Brooks was part of the global boom in simple holiday homes. Many Danes and Swedes have already spent their leisure time in the cabins, or Sommerhusealong the coast or along the forest. In 1960, Denmark had around 50,000 summer houses. By 1975, that number had tripled, according to the cabin crew.

Meanwhile, the close relationship between summer cottages Dacha) It was becoming a staple food for Soviet society in the Baltic countries and most of Central Europe. It seems like everyone, even the major architects, did they? Le Corbusierthe grand master of modernism created his Cabanon de Vacance at Roquebrune Cap Martin in southern France in the early 1950s. And in the United States, architect Paul Rudolph was behind a series of simple wooden structures in Florida keys.

The mushrooms in British cabins were part of the outcome of increased car ownership since the 1930s and holidays with the 1938 Salary Act, cabin crew explains. The latter led to the construction of a large number of seaside holiday camps with prefabricated accommodations.

Return to nature

Hird & Brooks cabins – some to buy, others to rent – Brooks was a Danish madness, so he drew on many study trips to Denmark. “His hero was a Danish architect, and his reference point was Danish architectural coverage, and his new wife helped him to embed the aesthetics of Danish design into his daily life,” the book explains.

“It was all simple and intelligent design, woodland setting and a close affinity with nature,” Halliday tells the BBC. “The entire Hird & Brooks team was fascinated and wanted to apply the same principles in the UK.”

Vince Jones

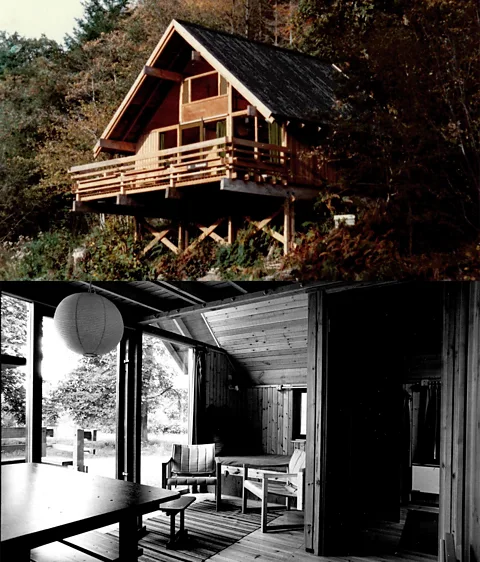

Vince JonesThe company completed its first holiday home in the early 1970s for Beerwood near Tenby, Pembrokeshire. These lodges of wood frames with exposed roof beams were covered in pine matchboarding, with tiled roofs and sun terraces. Inside, there are built-in beds and a galley kitchen. A palette of colours – blue-gray staining on the exterior wood surface, orange red window frames and doors – was inspired by a study trip in Denmark.

“The clearest Scandinavian influence is the use of wood, from large exposed structural beams to cedar cladding to built-in furniture, to small details such as wooden door handles and mounted coat hooks,” says Halliday. He also states that “architects designed their own and manufactured locally to save on wood stoves that were completely novel in the UK but common in Scandinavia but not available here.” And for all Welsh cabins, Brooks looked at the direction of the sun before placing each cabin on the plot.

The Forestry Commission, a national organisation that owns a huge strip of British countryside, brought Hard & Brooks to design holiday cabins at Deer Park in Cornwall, Keldy Castle in North Yorkshire, and Taynewt sites in Scotland. “For the Forestry Board cabins, it was all about giving it a sense of adventure,” Halliday says. “It’s an intended feature, and everything about the design reflects it.”

Ian Brooks Collection

Ian Brooks CollectionSome had an A-frame design, some had flat roofs, others had standard pitch roofs. It was also playful. Inside, the second bedroom had a staggered stack of three banks. “The high-level sleep and play platform provided forest views, while the large slat terrace with integrated benches blurred the distinction between indoors and outdoors. All of this was very eager to convey by the Forestry Commission,” the author of the cabin crew wrote. The soft furniture remained in the distinctive red and orange colorways the company had featured in its previous cabins.

By the end of the 1970s, at least 35 British companies had manufactured or promoted kit chalets, offering over 350 holiday parks. Meanwhile, on the continent, Dutch modernist architect Jacob Belend Baekma created the design for the Holiday Village Chain Centre Parks.

At this point, the British cabin movement was a partial response to the “white heat of technology” used by Prime Minister Harold Wilson in the 1960s to promote science. Bruce Peter, professor of design history at Glasgow School of Art, expands this with his book introduction. “At least, among people who are more politically progressive and culturally involved, there has been a rise in environmental awareness. This has been manifested in the growing interest in food, alternative medicine and natural life across the board.”

A simple life

And for Peter, benefiting from half-century hindsight, Hard & Brooks’ “holiday cabins” appear to be “very successful in standing the test of time. In the 1970s, environmentalism was primarily considered a concern for fringes, but moved to the mainstream in recent decades. And with reasonable maintenance, the exterior finish of their wood tended to disrupt the weather.” Furthermore, the type of outdoor-centric holidaymaking that the cabins intended has proven to be permanently popular, at least even within certain demographics.

The coming together of several factors means there is a renewed interest in the cabin now, Dalton tells the BBC. First, she cites the popularity of mid-century architecture and interior design among us who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s. It evokes nostalgic charm and reminds us of spaces and styles that we remember from childhood. ”

Then there’s the movement of a “small house.” The life of the cabin is appealing to people seeking a simpler and minimal lifestyle, and is immersed in nature. “Cabin Holidays offer a taste of that lifestyle without a full-time commitment,” says Dalton. “And of course, in this digital age, people are constantly looking for holiday images that can be instagrammed. These cabins are certainly covered with red painted windows and doors that make it impressive.”

Perhaps it’s not surprising that some of Brooks’ cabins have endured them. And some of them are still in the hands of the original family. “In most cases, the cabins appear to be in a near-real state,” the author writes. “Obviously, the owners like things like them.”