About 18 months ago, climate scientists started noticing that something was wrong. In March 2023, global sea surface temperatures began to rise. In a warming world, ocean temperatures are expected to rise further, but the rise in ocean temperatures is unusual since it occurred when the Pacific Ocean was in the neutral phase of a weather pattern known as El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). It was about. Sudden. In April 2023, sea surface temperatures set a new record. They did something similar in May.

As the months passed, the strange situation continued. In the summer of 2023, the world entered El Niño, the warm phase of ENSO. El Niño events typically result in warmer temperatures, but in late 2023 both sea surface and air temperatures rose enough to surprise scientists. one called That number is “absolutely bananas to devour.”

in essay appeared in nature In March of this year, NASA’s chief climate scientist Gavin Schmidt said, “It is humbling and a little alarming to acknowledge that no year has confounded climate scientists’ predictive abilities as much as 2023. ” he said.

Officially, El Nino ended in May 2024. However, global temperatures remain high. It is hoped that yet another record will be set this year.

Schmidt says scientists still can’t explain the unexpected rise in temperatures. When I spoke to him recently, he called the continued confusion “a little embarrassing” for researchers.

Scientists have identified several recent events that may have contributed to the unusually warm weather of the past year and a half. The first is a set of rules to reduce the sulfur content of fuel used in supertankers. Because sulfur dioxide pollution reflects sunlight, this change, while good for public health, could have led to increased ocean heating.

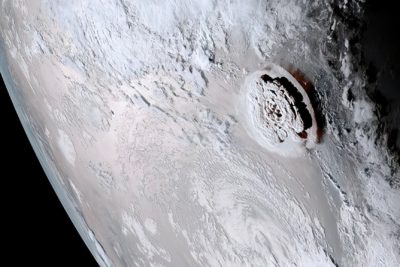

The second potential cause is the unusual eruption that occurred in January 2022. Volcanoes typically release sulfur dioxide, which causes temporary cooling. However, the eruption of the South Pacific submarine volcanoes Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha’apai may have spewed water vapor into the stratosphere, causing a warming effect.

Yet another possible cause is the solar cycle. The sun is currently at or near peak activity, which may also be pushing up temperatures.

But for now, Schmidt says, none of these developments, or even a combination of them all, appears to be enough to explain the heat. This raises several other possibilities. The recent increase in temperature may be the result of some development that has not yet been identified. Or it could mean the climate system is more unpredictable than thought. Or it could indicate that something is missing in climate models or that feedbacks are starting to amplify sooner than the models predicted.

I spoke with Mr. Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, via Zoom.

Gavin Schmidt.

NASA

Elizabeth Colbert: When did people like you start saying, “Okay, here’s something different than what I expected”?

Gavin Schmidt: In the spring of 2023, we began to see some eyebrow-raising events. Every year is warm now, so we expected 2023 to be another warm year, but it probably won’t be the warmest on record. So when records started being broken, first in the North Atlantic in March and April, June, then the global average in June, then throughout the rest of the year, and then in the fall on an absolutely ridiculously large scale. A record-breaking event occurred. — August, September, October, November — People started using adjectives that scientists don’t normally use.

At the end of 2023, we summed it up. This year was the warmest year on record, and it was on record. Our eyebrows were furrowed on our heads at this point. It was clear that all the predictions people had made at the beginning of the year were wrong. No matter which method was used, they were all wrong and had an error of about 0.2 degrees Celsius. It may not seem like a big deal, but it is.

There are two ways to react when your predictions are wrong. It can be said that the actual prediction was wrong. Or you could say, “No, we underestimated the uncertainty.”

So at the beginning of 2024, we thought: I wish we could get more information from people working on science about the different things that are happening. And perhaps more analysis will be done on internal variation. Some of that is happening, but not in a coordinated way. And in terms of assessing what actually happened in 2023, it’s still very much an amateur’s time.

Colbert: There was a whole list of things that people might have contributed.

Schmidt: right. One is regulatory changes by the International Maritime Organization that took effect in January 2020 to clean up the fuel used in shipping..

“Things are moving more volatile than we expected, which means future predictions could be even more off.”

Another event was the eruption of the Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha’apai volcano in the South Pacific Ocean, which was a very rare eruption. Large amounts of water vapor fall into the normally extremely dry stratosphere. It was such a new thing that people were saying, well, maybe that’s contributing.

People were also talking about the unusual behavior of dust in the Sahara desert and wind patterns in the North Atlantic. People were talking about the amount of pollution coming from China and India changing continuously over time. Maybe those conditions are changing faster than we expected. Pollution in the atmosphere is a cooling factor, so removing it causes warming.

The science that has been done has not spread evenly across all these areas. Many are focused on the impact of changes to maritime transport regulations. If we apply this to a climate model and estimate the temperature change, we would currently expect it to be around 0.05 to 0.08 degrees Celsius. [of warming per year], It will take 10 years to build up to about 0.1 degrees. It seems helpful, but not enough. And in the first paper that came out on volcanoes, they said, no, the volcanic pollution from normal cooling is still greater than the warming water vapor component. So now there is more to explain and less to explain.

We are still waiting for an assessment of emissions from China. We don’t know what the pollution is like.

The eruption of the underwater Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Haapai volcano in January 2022 produced water vapor that may have had warming effects.

NOAA

Colbert: Is there no data because there is no data collection method?

Schmidt: All prediction systems are currently using old input files. And for some of them there is a lot.

Colbert: [In March you wrote in Nature] “Global warming is already fundamentally changing the way the climate system works, much faster than scientists expected.” What did that mean? How do you feel about it now, six months later?

Schmidt: As I said earlier, there are two reasons why the prediction was wrong. One is that it lacks a driving element. The other is that you are underestimating the spread. Things are moving more volatile than we expected, and that means future predictions could be even more off. And in many ways, you could argue that things are getting even crazier, as the system is changing so that what happened in the past is no longer a good guide to what will happen in the future. And that’s a cause for concern. For example, we have huge expectations based on a huge industry and associated temperature anomalies. [El Niño].

Therefore, if we predict that [El Niño] African people then start planting different crops. Indonesian people start preparing for the dry season. If the connections between other parts of the world and what is happening in the tropical Pacific are changing, all previous practices and recommendations based on past relationships are likely to become useless. And if that is now the new normal, there is no new normal.

“The big uncertainty that will determine whether 2100 is a happy or not-so-happy place is our decisions about emissions.”

But if it turns out that the forcing from the volcano was a little bigger than we thought, then everything that came before is still fine, the history is fine, and we just need to make a fix for that one volcano. Right. But we haven’t been able to figure it out yet, so it’s a bit embarrassing for the community.

Colbert: How should I solve this?

Schmidt: I need to get updates for these input datasets.

We have 15 to 20 modeling groups so that we can consider exactly the questions that will be of interest to everyone. And we’re just twiddling our thumbs. Where is the data?

Colbert: If things are happening faster than expected, that can be very concerning.

Schmidt: that’s right. There are real decisions to be made and we are effectively providing people with information dating back to the last IPCC report in 2020. And while we’re probably fine with most things, I think we’d have more confidence if we had a process in place. This is where you update this information, not every day, but maybe once a year.

Colbert: What should the public know?

Schmidt: Temperatures will reach 1.5 degrees a little earlier than predicted four years ago. I think it’s 50-50 whether the temperature will reach 1.5 degrees this year. [NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies] Temperature records.

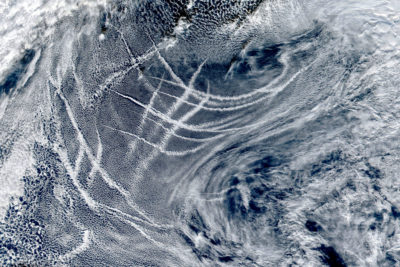

A satellite photo of a ship’s wake in the North Pacific Ocean. New restrictions on pollution have reduced cooling trails.

NASA

Colbert: I know people like you don’t want to answer questions like this, but I’ll ask anyway. Because you’re sitting at home and there’s probably a photo of your daughter behind you. As a father, what concerns you most about the data you’ve seen over the past year and a half?

Schmidt: My daughter was born in 2015. That means she could live until 2100. That is, the predictions we make will tell her that everything will be fine.

We study very small amounts of tea leaves to predict the future. What happened this month? What happened last month? What was happening in the Sahara? What was happening in Antarctica?

But the big uncertainty that will determine whether 2100 will be a happy or not-so-happy place is our decisions about what to do with emissions. And they trivialize the uncertainty we’re talking about here. This means 0.1 degrees and 0.2 degrees. Well, the difference in emissions is 1 degree, 2 degrees, 3 degrees. Therefore, it is an order of magnitude larger. And given the non-linearity of the impact, it would be a much, much larger impact.

make things happen faster [than anticipated] Reaching 1.5 degrees could prompt people to act more aggressively. And once it reaches 1.5 degrees, people may stop caring. It’s very difficult to predict that. I have a feeling that what we’re doing will affect these decisions, but I don’t know how it will affect these decisions. So my best plan is to do the best from a science perspective and hope that by learning more about this system, people will be able to make better choices. But clearly that’s hopelessly naive.

Colbert: People have to hold on to what they have.

schmidt: So if you really felt that people could make better decisions without information, you wouldn’t be a journalist. I won’t become a scientist. We will not believe in democracy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.