On Christmas Day 1971, for the first time in the roughly 300,000 years since Homo sapiens began walking, humanity’s demands on the Earth exceeded what the planet could provide in a year. This practice has continued and worsened over the past half century.

Since the early 2000s, the nonprofit organization Global Footprint Network hasEarth Overshoot DayThe day each year when humanity runs out of resources is called an “overshoot.” Currently, human society is consuming resources at a rate that would require 1.75 Earths to sustain it. This means that from August 1 of this year onwards, everything we consume will be added to our collective debt. In environmental economists’ words, “we’re in overshoot.”

The date itself is a useful concept to illuminate a larger issue: the reality is that Earth does not reset every year. In the science of planetary accounting, an overshoot is like charging your credit card for groceries after you’ve blown your monthly budget with online shopping: it can’t go on forever. Eventually, the bill will come due.

The debt we incur manifests itself in three main ways: waste accumulates, resources are depleted, and ecosystems degrade. As these impacts grow, the Earth’s ability to regenerate itself decreases. What that means in the long term remains to be seen, but as the debt piles up, the consequences are likely to become more severe. “We still live off the land,” says David Lin, chief science officer at Global Footprint Network. It’s easy to forget that, since modern life takes most of us away from the feel and smell of soil and crops. The concept of overshoot was, in a way, invented to remind us of the demands we place on the land.

Two researchers from the University of British Columbia, Matthijs Wackernagel and William Rees, have developed a metric called the Ecological Footprint. Early 1990s And with that, the idea of overshoot was born. They wanted it to be a “comprehensive sustainability index” — one that covers all of human impacts on the planet, not just a single aspect like greenhouse gas emissions. Wackernagel went on to co-found the Global Footprint Network to track and hopefully end the overshoot that his index uncovered.

Now, York University’s Ecological Footprint Initiative has taken over responsibility for aggregating and maintaining all the data needed to track, estimate, and forecast metrics that can be used to understand and correct overshoot, for every country in the world. These metrics include the Ecological Footprint (which represents the cumulative impacts, including carbon emissions, of humanity’s urban and industrial activities, such as logging, fishing, farming, building, and mining), and biocapacity, which reflects the ability of forests, fish, soils, landscapes, and mountainsides to recover from human demand. Comparing these two metrics will tell us whether we’re in overshoot territory, and if so, how badly.

Analyzing these numbers is no easy task: “To create this system, we stitched together about 47 million rows of input data,” says Eric Miller, an environmental economist who leads the Ecological Footprint Initiative, whose work stretches back to 1961.

These tables show Global Footprint Network and Miller’s team not only how much Earth has gone over budget this year, but also the accumulated debt. While the date of Overshoot Day has remained relatively stable over the past decade, the debt has continued to grow. Currently, Global Footprint Network estimates that the total debt is equivalent to 20.5 years of Earth’s life. This means that if all human activity were to stop at this point, Earth would not be able to finish repairing all the harm humans have inflicted on the planet until 2045.

Global Footprint Network

Miller noted that discussing things in terms of ecological footprints and overshoot not only helps quantify the problem of overconsumption, but also creates space to discuss comprehensive solutions to the overlapping environmental crises facing the planet. “That doesn’t just mean reducing absolute emissions, but also changing the way we use land and water,” Miller said. For example, it helps us understand that a particular climate solution, like biofuels for aviation, might solve one problem—carbon emissions—but also create other problems, like harvesting crops to feed planes instead of people.

From the perspective of the Ecological Footprint, climate change is not a fundamental crisis. Rather, it is just a symptom of an overshoot: emissions from overactive industries build up in the atmosphere and warm the planet. Biodiversity loss is another symptom of an overshoot, as are soil degradation, deforestation, and water scarcity.

However, the UN Climate Secretariat Earth OvershootBut the issue has yet to appear in international agreements or national policies. The various commitments drafted and adopted at the international, national, state, local and even corporate levels focus on global warming pollution. “So, not surprisingly, the world is paying a little bit of attention to the issue of greenhouse gas emissions,” Miller said.

But trying only to fight the symptoms of overshoot doesn’t make sense to Phoebe Bernard, a global change scientist at the University of Washington. “We all need to talk about the root causes and acknowledge and address them,” she says. Together with two colleagues, she founded the Stable Planet Alliance, a nonprofit organization focused on the problem of ecological overshoot and the actions and practices that have created it.

“We see the Earth as a food bank for humanity, or that its resources exist for our personal gain, rather than as a gift that the Earth has given us,” Bernard said.

Bernard and her colleagues argue: Addressing the overshoot requires addressing harmful behaviors And our belief in the pursuit of sustainable growth and profits.

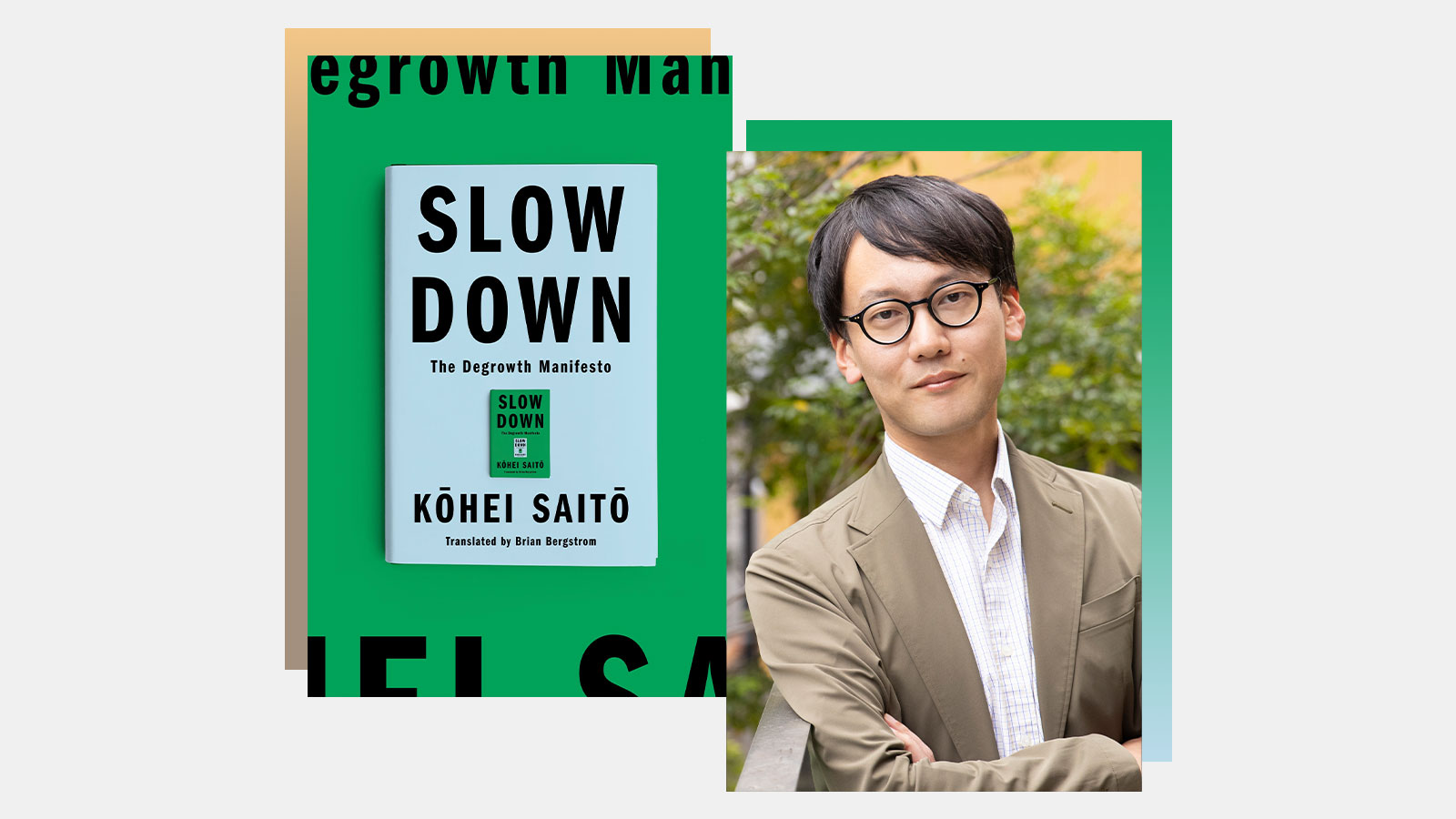

Slow Down and Do Less: A Q&A with the Author Who Introduced “Degrowth” to the Masses

They place a special emphasis on marketing as both the cause of the problem and a potential solution. The marketing industry has historically acted as an engine of overconsumption by making people crave things they don’t need or want. But, says Bernard, “what if we could use the tools of the marketing industry, which perfectly understands the science of behavior change, to reverse engineer humanity out of the impasse we’re in?”

The Global Footprint Network’s approach goes beyond raising awareness about Earth Overshoot Day: #MoveTheDate CampaignThe United Nations is promoting actions to reduce overshoot (and moving the date of Earth Overshoot Day closer to the end of the year), including promoting ecosystem restoration, 15-minute cities, green electricity, regenerative agriculture, etc. These overlap quite a bit with typical climate action, but discussing these actions from the perspective of overshoot highlights the fact that we cannot pursue infinite growth while pursuing our desire to have more and better things and achieve higher standards of living.

Both the Global Footprint Network and Barnard also address a controversial element that is said to be essential to fighting overshoot: population growth and pro-natalism. Barnard and her colleagues describe the desire to expand the human population as: In a post On Earth Overshoot Day, Global Footprint Network co-founder Wackernagel acknowledged the “brutal” history of efforts to curb population growth, but argued for reframing the debate in a “compassionate and productive direction” that enhances and advances sex and gender equality.

“Let’s move this conversation away from the old white men who have dominated the conversation so far and let the women of the world speak,” said Bernard, who believes that simply educating girls and women can lower birth rates and And many more benefits.

But ultimately, the biggest challenge in tackling overshoot, as with tackling symptoms like climate change, isn’t understanding the problem or the range of solutions that exist, but implementing them. Ultimately, when we think about what it would take to reduce overshoot and pay off our ecological debt, it’s a lot like considering what we could do to get our personal finances in order. “You can ask it in a mathematical sense,” says Lin, the Global Footprint Network scientist. But for each possibility, he adds: “Can you do it? Are you willing to do it?” That’s the question.

read more: