De Morgan Foundation Trustee

De Morgan Foundation TrusteeEvelyn de Morgan, an esoteric, pioneering, and lesser known painting of the Raphael tribe, explored the trauma and meaning of war and foreshadowed the fantasy art of the present day.

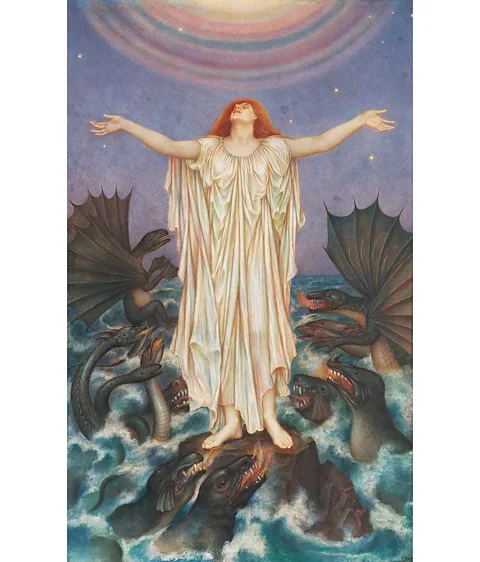

On a rocky beach full of lava-brown, smoke-sucking dragons surround miserably-looking prisoners and rescue angels from their suffering. The death of an oil painting by Evelyn de Morgan initially sees it as a scene from a book of apocalyptic revelation in the New Testament. But, depicted between 1914 and 1918, it is also more personal and critical. It is a story of all the misery and bondage of World War I, and a conflict between good and evil.

De Morgan Foundation Trustee

De Morgan Foundation TrusteeThe show coincides with the reopening of the De Morgan Museum in Barnsley, Yorkshire, followed by a major roof renovation. Increasing interest With this little-known artist. She tended to be devoured by her husband William (a potter and writer). He worked early in his career with textile designer William Morris. Much of what we know about De Morgan today comes from his sister Wilhelmina, who founded the De Morgan Foundation, but we thought it was fitting to publish the posthumous biographies of the couple under the title William De Morgan and his wife.

Still, Evelyn de Morgan deserves the late admiration of the art world. Slade graduates who worked in the tail of the Raphaelian movement undoubtedly brought a fat genre to new territory, creating unusually visionary and energetic tableaus. The women she portrayed were less passive than the women painted by her contemporaries, and not subject to male gazes, but as symbols of the agency. Like Iss John Everett Millése, in place of a drowned body floating in the river Opheliaor numbers with major currency Their lookswe meet skilled ones Magician who creates magic potions and Flying Super Heroine Who can throw rain, thunder, and lightning from your fingers.

These goddesses-like figures show the influence of classical art studied by De Morgan. Perfectly executed work like this Boreas and Oletia (1896) reveals her interest in myths reminiscent of Michelangelo and her mastery of human form.

From a composition perspective, it is easy to see the influence of Sandro Botticelli in the death of the Dragon The birth of Venus (1483-1485) De Morgan visited Florence. If De Morgan’s Haloed Angel reflects this idea of rebirth, reflecting the artist’s belief in the spiritual afterlife, the winged beast threatens to respond, death, always bite at people’s heels, overcoming them. Elsewhere in her work, death takes an alternative form: a Dark angel holding a scythe, Sea Monster Or – more diagonal – Sand Timer. It speaks to the temporality of life and is a symbolic symbol that gains even more moving emotion in subsequent works, conveying the collective trauma of living through World War I, which claims the lives of one million British people.

De Morgan Foundation Trustee

De Morgan Foundation Trustee“During World War I” [the De Morgans] Jean McMeekin, chairman of the De Morgan Foundation’s board, said “death has probably been forgotten recently,” and his own health was often poor. In a way, death has always been in the background. ”

De Morgan was a pacifist and her art became a form of behaviorism. in Mother of Peace (1907), response to the Board Wars, Knights plead for protection and peace. The poor man who saved the city (1901), wisdom and diplomacy have been proposed as alternatives to military intervention. later, Red Cross (1914-16), angels carry Christ crucified on a withered landscape stabbed in a Belgian war tomb. Perhaps Christian faith is at odds with the atrocities of war, but offers hope of red. “You should never praise war,” declared De Morgan in the results of the experiment (1909). “Automatic writing” Co-authored with my husband. “The devil invented it, and you can’t have that concept of fear.”

Good and evil

At this point, the idea of the powers of good and evil that act on ordinary people was widespread. “Spiritualism was extremely popular,” McMeekin quotes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (creator of Sherlock Holmes) as one of his most well-known supporters. Other world beliefs, she says, were “a era of many wars that were “probably the result of chaos and in addition to the massive changes that were taking place in society leading up to the turn of the century, as well as the world’s views.” Without a doubt, De Morgan was influenced by his mother-in-law, Sofia, a well-known spiritualist and medium. With so many lives lost, there was no doubt that we would believe we could reunite with those who left.

De Morgan Foundation Trustee

De Morgan Foundation TrusteeFor De Morgan, materialism is opposed to spirituality, and many of her works merge the pursuit of wealth with death. The crown is a repetitive motif of greed and misery, as worn by the dragon’s winged snake. in Earthbound (1897), the greedy king in a gold cape patterned with coins, is about to be overwhelmed by the angel of death. Prohibited gates (c.1910-1914), similar figures have been denied entry into heaven.

Because the future is so uncertain, De Morgan places the importance of spiritual fulfillment and happiness at the heart of much of her work. in Blindness and Cupidy chasing joy from the city (1897), for example, “Cupi” is personified as a person crowned figure who holds a treasure that drives away “joy” in the form of an angel. Here, like the death of a dragon, the central figure is chained together, suggesting a trapped soul.

in Prisoner (1907-1908), the prohibited window and wrists of women’s chains become a ratio of gender inequality in captivity, suggesting the support of De Morgans Universal voting rights (Evelyn was the signatories of at least two important petitions, and her husband was vice-president of the women’s suffrage men’s league). The theme is repeated again Luna (1885), the body bound to the ropes of the moon goddess, a mythical figure of female power, serves as a minor phor for the female struggle to influence her own destiny.

De Morgan Foundation Trustee

De Morgan Foundation TrusteeBaptized “Mary,” Evelyn later adopted her then-neutral middle name, as women’s art was not taken seriously. “She wanted to be considered on the same level as her male peers,” McMeekin said. “We can envision the enormous extent of self-ownership and determination in her desire to be a professional artist,” she adds, claiming that even De Morgan’s mother opposed her career choices.

Technically, De Morgan was also a pioneer. She experimented with polishing and rubbing golden pigments into her work to add depth and interest, and explored new painting techniques invented by her husband, created by polishing the colours with glycerin and spirit. Stylistically, she was also ahead of her time. The unconventional use of pink and purple, the bold ring of rainbow light foreshadows the psychedelic painting style of the 1970s, but her terrifying monsters don’t look out of place in modern fantasy art.

Art history has tended to portray women as mothers, beauty, or seducers of the Virgin, but De Morgan’s specific perspective on women again once again as figures of hope that will tell us an alternative bright future. in Tenebry’s Lux (Light of Darkness) (1895), for example, the figure of a woman holds an olive branch in her right hand, providing a path to peace. In the death of a dragon, the angel is surrounded by a magnificent rainbow: a symbol of spiritual fulfillment and freedom, and a joy (with the sky) that shows the promises of an afterlife.

De Morgan Foundation Trustee

De Morgan Foundation TrusteeIt’s a mistake to think of works such as the Death of the Dragon as “completely dark,” McMeekin said, “often pointing out [her] There are apocalyptic scenes, some faint or gentle paintings of hope.” In many ways, the death of a dragon is optimistic, expressing the sense that a war-like dragon is approaching its end. Shortly, she wrote in her diary.