This article is a collaboration between The Associated Press and Grist.

Jeremy Ford hates wasting water.

As foggy rain falls on the fields surrounding Homestead, Florida, Mr. Ford explains how much it costs to run a fossil fuel-powered irrigation system on his five-acre farm and how much it costs the planet. I lamented how bad it was.

Earlier this month, Ford installed an automated underground system that uses solar-powered pumps to periodically saturate crop roots, saving “thousands of gallons of water,” he estimated. Although initial costs may be high, he believes such climate-friendly investments are necessary expenses and more affordable than adding two more employees.

“It’s much more efficient,” Ford said. “We’ve been trying to figure out, ‘How do we do that?’ It requires minimal additional effort.”

Ayurella Horn-Muller / Grist

More and more companies are implementing automation in agriculture. This could ease the industry’s growing labor shortage, help farmers control costs and protect workers from extreme heat. Automation also has the potential to improve yields by increasing precision in planting, harvesting, and farm management, potentially alleviating some of the challenges of growing food in an increasingly warming world.

But many small farmers and producers across the country are not convinced. Barriers to adoption extend beyond high price to the question of whether the tool can do nearly the same job as the workers it replaces. Some of these same workers wonder what this trend means for them and whether machines will lead to exploitation.

On some farms, driverless tractors are churning acres of corn, soybeans, lettuce, and more. Although such equipment is expensive and requires new tools to master, row crops are very easy to automate. It will be much more difficult to harvest small, uneven and fragile fruits like blackberries, or large citrus fruits that require a little strength and dexterity to pull from the tree.

That doesn’t deter scientists like Xin Zhang, a biological and agricultural engineer at Mississippi State University. Working with a team at Georgia Tech, she applied some of the automation technology used by surgeons and advanced camera and computer object recognition capabilities to create a robotic berry-picking arm that can pick fruit without stickiness. I would like to create one. , a purple mess.

Scientists are working with farmers to conduct field trials, but Chan doesn’t know when the machine will be available to consumers. Although robotic harvesting is not widespread, there are several products on the market where we can see robotic harvesting taking place. orchards in washington to florida farm.

“This feels like the future,” Zhang said.

Is USDA’s “climate-smart” agriculture spending actually helping climate change?

But while she sees promise, others see problems.

Frank James, executive director of the grassroots agriculture organization Dakota Rural Action, grew up on a cattle farm in northeastern South Dakota. His family once employed several farm workers, but due in part to a lack of available labor, they had to downsize. Currently, much of the work is done by his brother and sister-in-law, although his 80-year-old father also occasionally pitches in.

They rely on the tractor’s autopilot, an automated system that communicates with satellites to steer the machine into orbit. However, it is not possible to determine the moisture level in the field, which can cause tools to become stuck or tractors to stall, requiring human supervision to function properly. This technology also complicates maintenance. For these reasons, he doubts that automation will be the “absolute” future of farming.

“You develop a relationship with the land, with the animals, with the place you’re producing. And we’re moving away from that,” James said.

Charlie Neighborgal/AP Photo

Tim Butcher grew up on a farm in Northern California and has been involved in farming since he was 16 years old. Dealing with weather problems like drought has always been a reality for him, but climate change is bringing new challenges with temperatures regularly reaching triple digits. A blanket of smoke ruins the entire vineyard.

Inspired by the ravages of climate change, compounded by labor issues, I founded AgTonomy in 2021, combining my agricultural experience with my Silicon Valley engineering and startup background. The company works with equipment manufacturers such as Doosan Bobcat to make automated tractors and other tools.

Since the pilot program began in 2022, Butcher said the company has been “inundated” with customers, primarily from vineyard and orchard producers in California and Washington.

The people who feed America are starving.

Farmers in the field say many are skeptical of new technology, but will consider automation if it makes their operations more profitable and their lives easier. Will Brigham, a dairy and maple farmer in Vermont, believes such tools could be a solution to the country’s agricultural labor shortage.

“Many farmers are struggling with labor,” he said, citing “intense competition” for “all-weather” jobs.

Brigham’s family farm has been using Farmblox, an AI-powered farm monitoring and management system, since 2021 that helps proactively resolve issues such as leaks in tubing used in maple production . Six months ago, he joined the company as a senior sales engineer to help other farmers implement similar technology.

Charlie Neighborgal/AP Photo

Removing the ears of corn was once a rite of passage in the Midwest. The teens waded through a sea of corn to remove the ears (the yellow flap-like part at the tip of each stalk) to prevent unwanted pollination.

Extreme heat, drought and torrential rains make this labor-intensive task even more difficult. And now, immigrant farmworkers often do it, sometimes for 20 hours a day. That’s why Jason Cope, co-founder of agricultural technology company Power Pollen, believes mechanizing arduous tasks like detasseling is essential. His team has developed a tool that allows a tractor to collect pollen from male plants without having to remove them. It can then be saved for future crops.

“Perfect timing of pollen arrival explains climate change,” he says. “And it takes extraordinary effort to make that happen.”

Charlie Neighborgal/AP Photo

PowerPollen intern Evan Mark prepares a pollen applicator on Thursday, Aug. 22, 2024, near Ames, Iowa. Charlie Neighborgal/AP Photo

Charlie Neighborgal/AP Photo

This machine collects pollen from corn ears and collects it in a container. Charlie Neighborgal/AP Photo

Charlie Neighborgal/AP Photo

Eric Nicholson, who previously worked as a farmworker organizer and now runs Semirello de Ideas, a nonprofit focused on farmworkers and technology, believes that automation will lead to jobs being lost. He said he has heard from concerned farmworkers. Others have expressed concerns about the safety of working with autonomous machines, but are afraid to raise the issue for fear of losing their jobs. He wants the companies that make these machines and the farm owners who use them to put people first.

Luis Jimenez, a New York dairy worker, agrees. He described one farm that uses technology to monitor disease in cattle. Using such tools, you may be able to identify infections faster than dairy workers or veterinarians.

It also helps staff find out what’s going on with the cows, Jimenez said in Spanish. But fewer people are needed on farms, he said, potentially putting additional pressure on those who remain. This pressure is further increased by automated technologies such as video cameras used to monitor employee productivity.

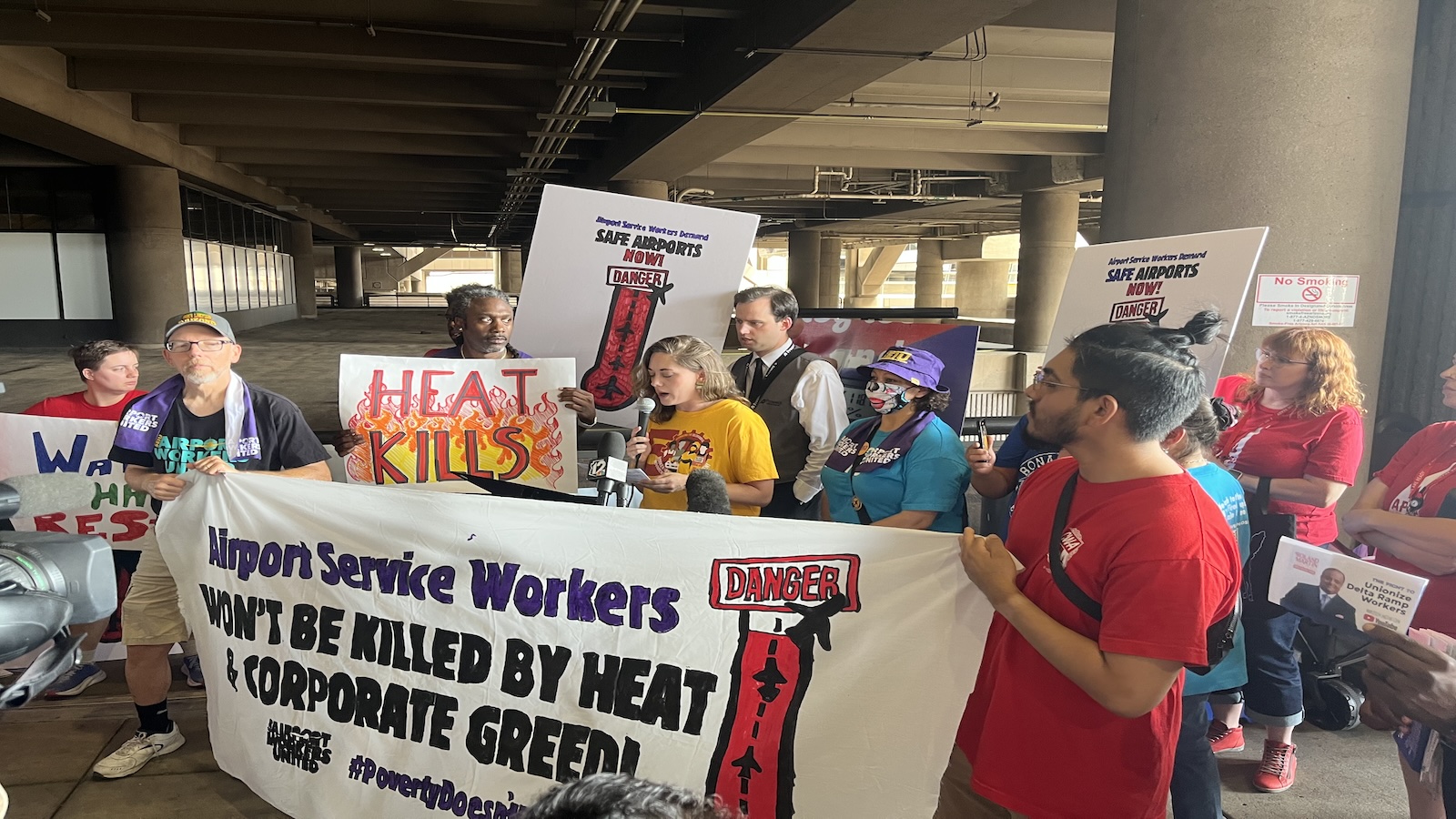

Workers across the U.S. rally after a series of heatstroke-related deaths

Jiménez, who advocates for migrant farm workers with the grassroots organization Alianza Agricola, said automation “can become a tactical tactic for the bosses, so people are afraid to demand their rights.” After all, he added, robots are “machines that don’t ask for anything.” “We don’t want to be replaced by machines.”

Associated Press writers Amy Taxine in Santa Ana, California, and Delaney Pineda in Los Angeles contributed to this report. Walling reported from Chicago and Horn Mueller reported from Homestead., Florida.