Whenever a federal agency wants to develop a Wyoming project, it must first pass through the crystal, including oil and gas leases, pipelines, dams, power lines, solar arrays. If a historic conservation officer in North Arapaho and tribes, or a historic conservation officer in North Arapaho tribes, or a new wind farm is proposed, for example, she will determine whether the project will affect the tribal area.

“It’s a challenging job, but I feel it’s a really important job,” C’Bearing said. “I am grateful to be able to do this and try to maintain and protect what we have, in my best possible ability.”

The scope of C’Bearing extends beyond her home on Windriver’s reservations to the route taken by tribal members between any land transferred by the treaty, removal processes, burial sites and religious sites. That means reviewing projects in 16 states, including Wisconsin to Montana, New Mexico, Arkansas and all the points in between. The traditional homelands of northern Arapaho and other indigenous peoples were forced by the United States to expand west. Because of that range, hundreds of federal proposals and reports flood her email inbox each week. 227 other thpo I work for each country. Many overlap with historical homes.

Tribal historic preservationists, like C’Bearing, are the primary line of defense against destructive federal projects, relying on a variety of skills, ranging from traditional ecological knowledge to cultural and historical knowledge of places and landscapes. Now their work is under threat.

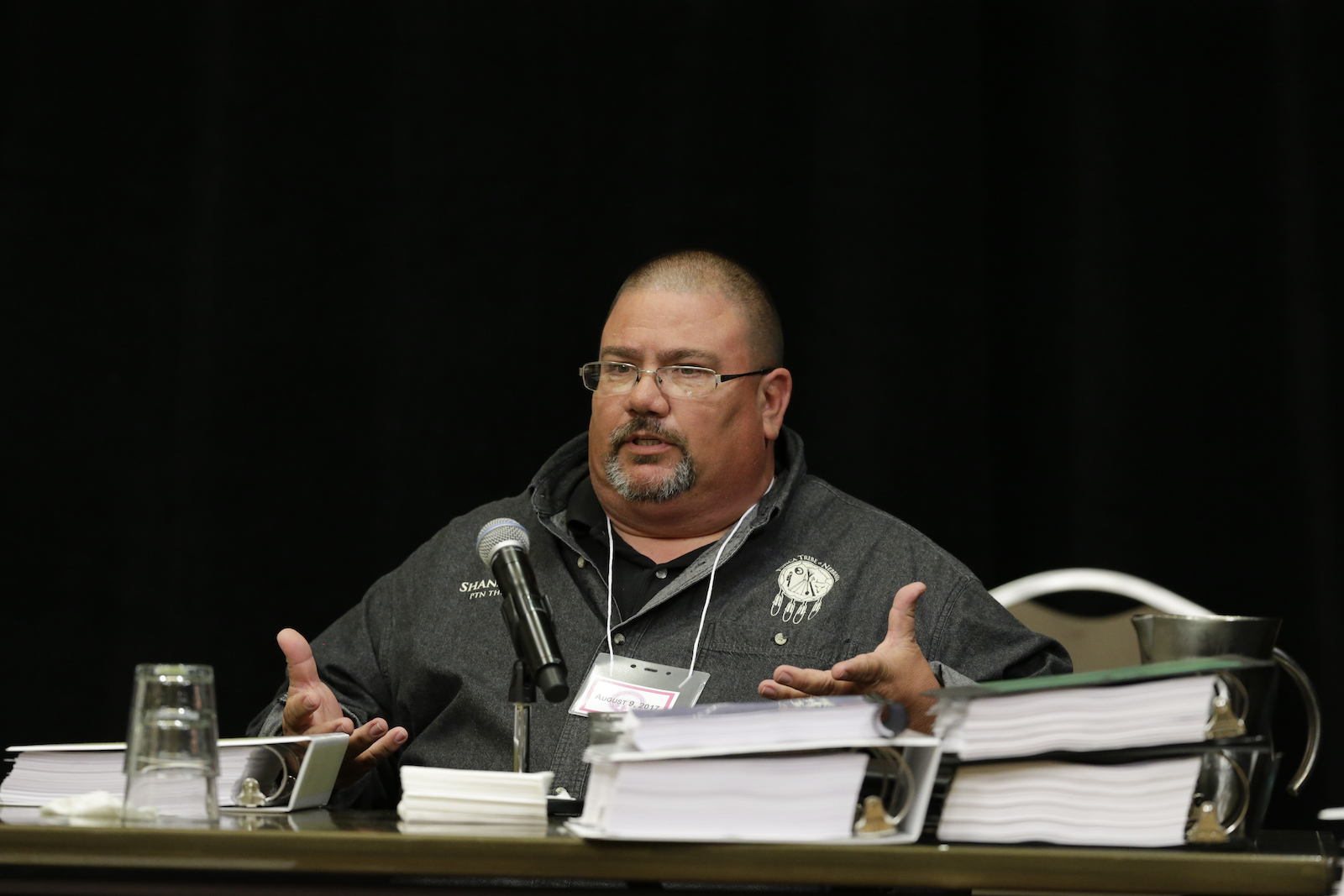

Scott Sonar / AP Photo

President Donald Trump in January National Energy Emergency has been declared To speed up the development of fossil fuel projects, mines, pipelines and other energy-related infrastructures It saves time Federal agencies must notify Indigenous people before starting a project. Now like Trump Budget proposal for 2026 Through Congress, we pass through the funds that support it. The national THPO program is brave 94% budget cut. In addition, the Trump administration has not yet distributed the THPO fund promised for 2025.

Traditionally, reviews of projects like C’Bearing have 30 days. We review 30-day federal reports, conduct site visits, identify artifacts and burial sites, and work with tribal members from other tribes. According to C’Bearing, the windows were already tight, but under Trump’s energy emergency, the deadline is seven days. And as the year progresses, C’Bearing’s budget has evaporated. If the administration does not release the already promised THPO funds, she will quit her job in September.

“If this is the moment when it breaks the system, there’s nothing to catch THPO,” said Valerie Grossing, executive director of the National Association of Tribal Historical Preservation Officers.

The THPO program was born Requirements established by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 – Laws responsible for the conservation and protection of US historical and archaeological resources. At the time, public concerns about historic locations being altered or destroyed by federally funded infrastructure and urban renewal projects urged the federal government to take legislative action. The law requires all federal agencies to identify the impact of the project on areas important to the state and tribe, and notify the public of those impacts. However, indigenous peoples play a particularly important role. Agency must consult with tribes, whether the project is on a federally recognized Indian reservation. That warning falls inside The broader context of treaty law and rightsand, as well as the responsibility for federal trust, it requires agencies to put “honest efforts” into consultations.

If THPO conducts the analysis and finds there is no risk of federal projects affecting cultural or historical resources, the plan will move forward. If THPO determines there is a risk, the tribe, federal agencies and states will form a formal agreement explaining how the impact will be resolved or mitigated. That part of the process can take years.

Nati Harnik / AP Photo

However, due to the significantly shorter review period, THPO needs to make tough choices when prioritizing “emergency” projects at the cost of hundreds of weekly reports, existing backlogs, and other sacrifices. This means that tribes have voices about how projects are determined in their homelands, putting countless cultural and historical places at risk. Many of these sites are undeveloped wilderness areas, like Pe’sla in the Black Hills (a sacred ritual place for Sue, Lakota and other countries). Exploratory drilling of graphite. Many of the world’s most resilient forests, like Pesla, are protected by indigenous peoples, and offer the benefits of climate change mitigation by storing carbon.

“In many cases, some of these areas need to be looked deeper and rechecked, triple checked, and inter-tribal adjustments as needed,” said Rafael Wasssack, THPO of the Civic Potawatomi Tribe. “It’s pretty unrealistic to do a good job just before the window.”

As of April, 186 project The emergency designation has been cleared to begin construction. The designation includes controversial projects Line 5 In Minnesota, prompt Seven Indigenous Peoples Leave From federal negotiations. There are 15 states sued the government There is no energy emergency, and the declaration is Illegally bypass additional reviews of federal projectsenvironmental impacts and evaluation of endangered species.

“My concern is that everyone will use emergency declarations in some way in all of these projects, and we will only be bombarded with those tons,” C’Bearing said. “This is another addition that we need to pay attention to hundreds of other things we do here.”

But beyond the timeline of truncated reviews, the funds are gone. The funds approved and allocated in Congress in 2025 are still held by the Bureau of Management and Budget, or OMB, awaiting additional reviews by the Trump administration. Neither OMB nor the White House responded to requests for comment on the story. Home Office officials said pending financial support obligations, including grants, are being reviewed to comply with Trump’s recent executive order.

“If this continues, they will need to take on legal remedies to enforce the law and take oversight measures. That’s not a proposal, it’s not an option. The law must spend these funds.” She is a member of the House Committee on Approximate Budget. “It’s wrong to maintain funds for tribal governments. Strategically and legally. Many tribes have been waiting decades for basic investments in schools, housing and infrastructure. And now, even when the funds are approved by Congress, they are forced to wait again for politically motivated delays that violate the law.”

Despite the importance THPO plays for Indigenous peoples, few tribes are able to dedicate additional funds to maintain these roles. As the program was designed, the majority is entirely dependent on federal funding, Grussing said, and that allocation provided only one staff member per tribe, an average of one staff member per THPO office.

The US government stole the Black Hills. Now it makes them clear.

“It was difficult for tribes to prioritize historic preservation than usual. It’s usually quite difficult, but now we see similar effects on tribal education, health and housing,” says Grussing. Trump’s proposed 2026 budget will cut $901 million from the Indian Affairs Bureau and the Indian Education Bureau. “It’s not realistic to expect tribes to step up and prioritize historic preservation during this time.”

Funding cuts passed to multiple points in tribal projects require tribes to fund health and safety and fund the THPO program. The concern for Wahwassuck is that if multiple tribes lose staff working on consultation requests with the THPO, conditions will effectively return before charging in advance, as in the 1960s. In that world, tribal states will not have the opportunity to intervene or protect land or cultural resources.

“We have earned a lot of benefits from the blood and bones of our ancestors, and from the land that our tribes had to hand over and be excluded,” Wahwassack said. “I have heard that this administration has said quite regularly that it recognizes tribal sovereignty and wants to respect trust and treaty responsibility. However, these funding measures are directly in opposition to these statements.”